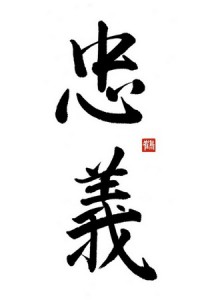

忠義 – Loyalty

During the last week of October 2013, I had the opportunity and the pleasure to attend Fazıl Say’s Tokyo tour, Tokyo International Film Festival featuring Reha Erdem’s films and visit my dear friend Engin Yenidunya. In that very week, two separate hurricanes and one earthquake hit Tokyo. It was in the midst of very strong winds and unforgiving rain that I witnessed an old municipality worker diligently cleaning a foot bridge.

During the last week of October 2013, I had the opportunity and the pleasure to attend Fazıl Say’s Tokyo tour, Tokyo International Film Festival featuring Reha Erdem’s films and visit my dear friend Engin Yenidunya. In that very week, two separate hurricanes and one earthquake hit Tokyo. It was in the midst of very strong winds and unforgiving rain that I witnessed an old municipality worker diligently cleaning a foot bridge.

I am dedicating this article to the pure dedication of thousands of these noble soles that keep a country of 130 million and the mega city of Tokyo ticking over with such precision and order.

“Loyalty” simply defined as “keeping one’s word and acting in accordance with expectations one projects” has been a topic of discussion between philosophers, sociologists, theologians, warriors and statesmen.

The beauty and connotations of loyalty is put through examples and studies through history although some may define it by the opposite concepts of betrayal, and crime and punishment.

Rome’s notice of pacta sund servanda and, therefore, the west’s attention to loyalty is evident in the dialogues of Plato, student of Socrates. Similarly, the importance and consideration donated to loyalty by the Asian continent is marked by philosophers from Mao to Conficius, by law systems of the oldest known laws of the Sumerians, and by Kuran in the Islamic civilisations led through the prophet Mohammed’s teachings.

Nevertheless, not one system or society has “lived” loyalty and devotion as honest and as sincere as the Japanese. Dedicated devotion to duty; faithful loyalty to parents and forefathers; faultless commitment to the uttered word, the sacred, friends and family; and the faithful allegiance to virtues and masters is lived through the Japanese culture with straightforward honesty and sincere integrity. You may now think that my statements are made through a bias and affectionate viewpoint. However, the western consensus on the living fibres of loyalty in the Japanese culture is the same through numerous nonbiased and objective studies such as the observations made by the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier (15549-1551).

Nevertheless, not one system or society has “lived” loyalty and devotion as honest and as sincere as the Japanese. Dedicated devotion to duty; faithful loyalty to parents and forefathers; faultless commitment to the uttered word, the sacred, friends and family; and the faithful allegiance to virtues and masters is lived through the Japanese culture with straightforward honesty and sincere integrity. You may now think that my statements are made through a bias and affectionate viewpoint. However, the western consensus on the living fibres of loyalty in the Japanese culture is the same through numerous nonbiased and objective studies such as the observations made by the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier (15549-1551).

It is important to investigate the basic theological and cultural principals that govern legal and moral systems of society in order to understand this notion. In japan, the initial consciousness of loyalty and commitment to parents and forefathers is imprinted by deep rooted shamanic and Shinto principals. On an island where life conditions are difficult, the individuals’ notion of devotion to parents who give them life, loyalty to their forefathers, and honouring them with real actions, extending loyalty to family and friends and society has constructed the basis in developing and maintaining social security, working legal systems and economical protection. Practical implications of Conficius, Bushido and Zen philosophies have embossed loyalty, devotion and responsibility to the very genes of the Japanese society.

Chuugi (忠義) means loyalty and is one of the seven principles of Bushido (武士道- Way of the Warrior). Chuugi is made up of two characters (忠義) and the first character is a composition of the “heart” and the “center/inner” (忠) positioned on top of each other. Therefore, even the very first character includes concepts of the “inner/center” and heart/soul/conscience. This first character denotes commitment, loyalty and devotion. The second character, Gi (義), denotes justice, honesty and truthfulness.

Chuugi (忠義) means loyalty and is one of the seven principles of Bushido (武士道- Way of the Warrior). Chuugi is made up of two characters (忠義) and the first character is a composition of the “heart” and the “center/inner” (忠) positioned on top of each other. Therefore, even the very first character includes concepts of the “inner/center” and heart/soul/conscience. This first character denotes commitment, loyalty and devotion. The second character, Gi (義), denotes justice, honesty and truthfulness.

It is thus possible to seize the components of the very meaning of loyalty from the subtle beauties in the depths of the Japanese language. These components are truthfulness, honesty, dedication and devotion that we have in our consciousness and the centres of our souls.

Up to here, I humbly tried to handle the theological, philosophical, cultural and linguistic components of loyalty and its theoretical presence in the Japanese society. In fact, it is possible to extract all these theoretical arguments of loyalty from all societies and their virtuous teachings. What distinction here is the way loyalty feeds life, finds life and becomes life in the Japanese society.

Bushido and Zen Budhishm that got shaped by Bushido is built upon magnificently bold teachings of loyalty and devotion. One must endeavour with all one’s good will and might in order to keep one’s word and meet what is expected. Duties must be performed and honour must be protected at all costs even at the cost of life. For a Samurai may not continue with living in the contrary. Japanese history is filled with such virtuous behaviour that is impossible to understand and even be stamped as senseless waste of life with today’s way of thinking.

The tombs of the 47 Ronin (Chuushingura -忠臣蔵) are today visited by thousands of Japanese. They committed seppuku (harakiri) after taking the revenge of their master who had been unfairly forced to seppuku (harakiri). The vengeance had taken two whole years of planning in total abstinence.

Hachiko, the loyal dog friend of Professor Ueno, has a special place in the hearts of the Japanese people. Hachiko waited for his owner friend, after his death, every day for 9 years at the same time at Shibuya station. When Hachiko died his statue was erected at this station in order to honour his dedication and loyalty. (I would strongly recommend the viewing of the 1987 movie Hachiko Monogatari)

Hachiko, the loyal dog friend of Professor Ueno, has a special place in the hearts of the Japanese people. Hachiko waited for his owner friend, after his death, every day for 9 years at the same time at Shibuya station. When Hachiko died his statue was erected at this station in order to honour his dedication and loyalty. (I would strongly recommend the viewing of the 1987 movie Hachiko Monogatari)

In 1600, General Mototada Torii defended the Fushimi Fortress together with his mere two thousand militia against a staggering forty thousand strong invading troops. General Ishida’s heroic and fearless fight helped his master Tokugawa with time to strategise his army into victory of the Sekigahara Battle. The Sekigahara Battle has ended the civil war (Sengoku Jidai – 戦国時代) and largely marked the beginnings of the Tokugawa Shogunate. General Ishida, who committed seppuku at the end of his defeat, was hence instrumental in ending civil wars that raged across Japan. His only heritage was the written note he left for Tadamasa stating “It is not the way of the warrior to fall into the pit of shame with excusing himself of death. Devotion of the warrior to his master is an unwavering principle. To be able to sacrifice my life for my master is a dream that I’ve had for years and indeed an honour to me.”

The sincere application of Loyalty through thousands of years has become genetically imbedded into the Japanese culture and has become the very essence and foundation of the Japanese culture. Devotion and loyalty are evident in today’s achievements in work, economic success and social concord. An individual’s lifetime devotion to one company may be perceived as credulity by the western white-collar culture. However, individuals are not perceived as mere workers in Japanese companies. It is expected to show a sincere sense of mutual respect at the beginning of each contract. The company becomes the family union in which individuals are appreciated members. During the New Year speeches, bosses of companies do not address workers but their families for their being in their lives. This structure and phenomenon is called Marugakae (total-man, 丸抱え) and it brings about a mutual devotion and loyalty through a sense of totality, unity and consistency which may appear senseless in the West.

The sincere application of Loyalty through thousands of years has become genetically imbedded into the Japanese culture and has become the very essence and foundation of the Japanese culture. Devotion and loyalty are evident in today’s achievements in work, economic success and social concord. An individual’s lifetime devotion to one company may be perceived as credulity by the western white-collar culture. However, individuals are not perceived as mere workers in Japanese companies. It is expected to show a sincere sense of mutual respect at the beginning of each contract. The company becomes the family union in which individuals are appreciated members. During the New Year speeches, bosses of companies do not address workers but their families for their being in their lives. This structure and phenomenon is called Marugakae (total-man, 丸抱え) and it brings about a mutual devotion and loyalty through a sense of totality, unity and consistency which may appear senseless in the West.

This observable sense of loyalty, that I tried to explain, withholds the old municipality worker from stopping to clean the walk ways during hurricanes and exhibits strong feelings of work ethics, social responsibility, willing contribution and self respect and worth, that is much more deep rooted and superior than in the West and the Middle East

Two childhood friends spend their youth serving in the same castle as Samurai. They enjoy watching the full moon (Tsukimi -月見) while coming up with Haiku in response to each other. One of them is posted in another post somewhere else. Before his departure, he takes the oath that “In honour of our friendship, no matter what happens, I will return for our Tsukimi and read Haiku with you in the middle of each Autumn.” Indeed, a few years pass by when he visits his friend during the full moon in the middle of each autumn for their special ritual.

Two childhood friends spend their youth serving in the same castle as Samurai. They enjoy watching the full moon (Tsukimi -月見) while coming up with Haiku in response to each other. One of them is posted in another post somewhere else. Before his departure, he takes the oath that “In honour of our friendship, no matter what happens, I will return for our Tsukimi and read Haiku with you in the middle of each Autumn.” Indeed, a few years pass by when he visits his friend during the full moon in the middle of each autumn for their special ritual.

Ten years pass by and on the tenth year, the first samurai gets the chance to pay his friend a surprise visit. He is taken to a tomb when he excitedly asks for his friend. His beloved friend had been executed for disloyalty five years earlier. His last wish to inform his childhood friend that he would be unable to keep his word had been denied as he was branded disloyal and dishonest!

With a heart-rending feeling, The Samurai understands that, for the past five years, he was being visited by the soul of his childhood friend who was yearning to keep to his word. With a tear coming down his cheek, he prays for the soul of his friend, thanks him and excuses him of his promise.

Ülkemizde Internet üzerinden işlenen suçlarla mücadele konusunda özel hüküm getirme ve Avrupa Birliği mevzuatı ile uyum sağlama ihtiyaçları kabul tarihi 4 Mayıs 2007 olan 5651 Sayılı Internet Ortamında Yapılan Yayınların Düzenlenmesi ve Bu Yayınlar Yoluyla İşlenen Suçlarla Mücadele Edilmesi Hakkında Kanun’la (“5651 Sayılı Kanun”) giderilmeye çalışılmıştır.

Ülkemizde Internet üzerinden işlenen suçlarla mücadele konusunda özel hüküm getirme ve Avrupa Birliği mevzuatı ile uyum sağlama ihtiyaçları kabul tarihi 4 Mayıs 2007 olan 5651 Sayılı Internet Ortamında Yapılan Yayınların Düzenlenmesi ve Bu Yayınlar Yoluyla İşlenen Suçlarla Mücadele Edilmesi Hakkında Kanun’la (“5651 Sayılı Kanun”) giderilmeye çalışılmıştır. İfade hürriyetinin ve haber alma hürriyetinin temel birer insan hakkı olarak kabul edilmesinin ve bu ilkelerin evrensel insan hakları beyannameleri ile anayasalara girmesinin üzerinden uzun zaman geçti. Bu temel hak ve hürriyetlerin kullanılabilmesinin ve ekonomik insani gelişimde fırsat eşitliği gibi daha birçok faydası olan Internet’e erişim hakkı da artık günümüz dünyasının tartışmasız

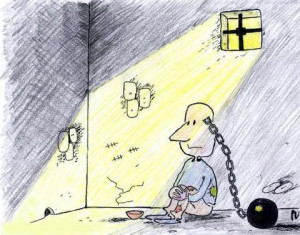

İfade hürriyetinin ve haber alma hürriyetinin temel birer insan hakkı olarak kabul edilmesinin ve bu ilkelerin evrensel insan hakları beyannameleri ile anayasalara girmesinin üzerinden uzun zaman geçti. Bu temel hak ve hürriyetlerin kullanılabilmesinin ve ekonomik insani gelişimde fırsat eşitliği gibi daha birçok faydası olan Internet’e erişim hakkı da artık günümüz dünyasının tartışmasız  YouTube’a Türkiye’den erişim, 2007 ile 2010 yılları arasında verilen çeşitli mahkeme kararlarıyla toplamda iki yıl kadar engellenmişti. YouTube’un kapatılmasına sebep olan içerikler, dünyanın her yerinden ulaşılabilir iken, devekuşunun kafasını kuma gömmesi misali absürd bir biçimde sadece Türkiye’den ulaşılamaz hale getirilmiştir. (

YouTube’a Türkiye’den erişim, 2007 ile 2010 yılları arasında verilen çeşitli mahkeme kararlarıyla toplamda iki yıl kadar engellenmişti. YouTube’un kapatılmasına sebep olan içerikler, dünyanın her yerinden ulaşılabilir iken, devekuşunun kafasını kuma gömmesi misali absürd bir biçimde sadece Türkiye’den ulaşılamaz hale getirilmiştir. ( 2013 senesi yaşananlar, özellikle

2013 senesi yaşananlar, özellikle  İşte bu çok açık ve çarpıcı örnekler de göstermektedir ki, kanun ve uygulama çok ciddi sorunlarla doludur. Mevzuatımızı nasıl düzeltebiliriz ve yargımızı nasıl bu konuda belli bir noktaya getirebiliriz? Bu bizim derhal ele almamız gereken bir sorundur ve bir süredir yaptığım da budur.

İşte bu çok açık ve çarpıcı örnekler de göstermektedir ki, kanun ve uygulama çok ciddi sorunlarla doludur. Mevzuatımızı nasıl düzeltebiliriz ve yargımızı nasıl bu konuda belli bir noktaya getirebiliriz? Bu bizim derhal ele almamız gereken bir sorundur ve bir süredir yaptığım da budur.

Fakat bu, hem bir mentalite değişimi, hem de bu eko-sistemin üzerinde serpilebileceği bir hukuk ve yargı altyapısı değişimi gerektirmektedir. Vatandaşı dijital okur-yazar yapmak, kendini dijital olarak maruz kalabileceği zararlı içerikten veya tercih dışı içerikten koruyabilir, Internet’ten faydalanabilir hale getirmek yerine, Internet’i ve sosyal medyayı sansürlemek, reşit ve mümeyyiz vatandaşı çocuk yerine koyarak Internet alanını onun adına şekillendirmek, Internet ve sosyal medya süjelerini hapisle ve sair yöntemlerle cezalandırmak, elektronik ticaret ve mahremiyet mevzuatlarını gereği gibi düzenlememek veya hiç çıkarmamak Türkiye’mizin önündeki tarihi bir fırsat olan “teknoloji devrimini” de önceki devrimleri kaçırdığımız gibi kaçırmak anlamına gelecektir.

Fakat bu, hem bir mentalite değişimi, hem de bu eko-sistemin üzerinde serpilebileceği bir hukuk ve yargı altyapısı değişimi gerektirmektedir. Vatandaşı dijital okur-yazar yapmak, kendini dijital olarak maruz kalabileceği zararlı içerikten veya tercih dışı içerikten koruyabilir, Internet’ten faydalanabilir hale getirmek yerine, Internet’i ve sosyal medyayı sansürlemek, reşit ve mümeyyiz vatandaşı çocuk yerine koyarak Internet alanını onun adına şekillendirmek, Internet ve sosyal medya süjelerini hapisle ve sair yöntemlerle cezalandırmak, elektronik ticaret ve mahremiyet mevzuatlarını gereği gibi düzenlememek veya hiç çıkarmamak Türkiye’mizin önündeki tarihi bir fırsat olan “teknoloji devrimini” de önceki devrimleri kaçırdığımız gibi kaçırmak anlamına gelecektir. Ekim 2013’ün son haftası Fazıl Say’ın Tokyo Turnesi’ne ve Reha Erdem’in filmlerinin de yer aldığı Tokyo Uluslararası Film Festivali’ne katılmak, sevgili dostum Engin Yenidünya’yı ziyaret etmek amacıyla Tokyo’da bulundum. O hafta iki ayrı tayfun ve bir deprem Tokyo’yu vurdu. Tayfun devam ederken, şiddetli yağmur ve fırtına esnasında yaşlı bir belediye işçisi bir üst geçidi merdiven korkuluklarına kadar siliyor ve temizliyordu. Bu yazımı Tokyo gibi bir mega metropolü, Japonya gibi 130 milyonluk bir ülkeyi bu kadar kusursuz ve temiz tutan o belediye işçisi gibi sadakatle görevine sarılan binlercesinin asil ruhuna ithaf ediyorum.

Ekim 2013’ün son haftası Fazıl Say’ın Tokyo Turnesi’ne ve Reha Erdem’in filmlerinin de yer aldığı Tokyo Uluslararası Film Festivali’ne katılmak, sevgili dostum Engin Yenidünya’yı ziyaret etmek amacıyla Tokyo’da bulundum. O hafta iki ayrı tayfun ve bir deprem Tokyo’yu vurdu. Tayfun devam ederken, şiddetli yağmur ve fırtına esnasında yaşlı bir belediye işçisi bir üst geçidi merdiven korkuluklarına kadar siliyor ve temizliyordu. Bu yazımı Tokyo gibi bir mega metropolü, Japonya gibi 130 milyonluk bir ülkeyi bu kadar kusursuz ve temiz tutan o belediye işçisi gibi sadakatle görevine sarılan binlercesinin asil ruhuna ithaf ediyorum. Ancak hiçbir toplum ve sistem, sadakati, ahde vefayı Japon toplumu kadar dürüst ve samimi biçimde yaşamamıştır ve bugün de yaşamamaktadır. Vazifeye sadakat, ebeveyne sadakat, atalara sadakat, verilen söze sadakat, emanete sadakat, dosta sadakat, eşe aileye sadakat ve bir savaşçı olarak erdemlere ve efendiye olan sadakat Japon kültüründe tarihin her döneminde benzersiz bir adanmışlık, samimiyet ve kendine karşı dürüstlük ile yaşanmıştır. Bu tespiti sübjektif bir düşkünlükle sadece ben yapıyorum zannedilmesin. 1549 – 1551 yılları arasında Japonya’da misyonerlik yapan Cizvit Francis Xavier’dan bugüne kadar Japonya hakkında ciddi ve önyargısız bilgi edinen ve değerlendirme yapan tüm batılılar da bu durumu tespit etmişlerdir.

Ancak hiçbir toplum ve sistem, sadakati, ahde vefayı Japon toplumu kadar dürüst ve samimi biçimde yaşamamıştır ve bugün de yaşamamaktadır. Vazifeye sadakat, ebeveyne sadakat, atalara sadakat, verilen söze sadakat, emanete sadakat, dosta sadakat, eşe aileye sadakat ve bir savaşçı olarak erdemlere ve efendiye olan sadakat Japon kültüründe tarihin her döneminde benzersiz bir adanmışlık, samimiyet ve kendine karşı dürüstlük ile yaşanmıştır. Bu tespiti sübjektif bir düşkünlükle sadece ben yapıyorum zannedilmesin. 1549 – 1551 yılları arasında Japonya’da misyonerlik yapan Cizvit Francis Xavier’dan bugüne kadar Japonya hakkında ciddi ve önyargısız bilgi edinen ve değerlendirme yapan tüm batılılar da bu durumu tespit etmişlerdir.